Post by clovis d'aubigne on Dec 29, 2010 15:10:06 GMT -8

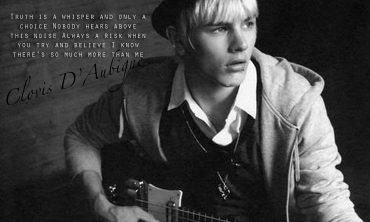

clovis philippe d’aubigne

[/size]

name: katja

age: nineteen

gender: female

writing experience: many, many moons

how’d you find us?: I hijacked a train and jumped on top of the admins…. or something.

a favorite book: Shattered Justice by Karen Ball

other character(s): Neil, Lucas, Ewan, Julianna, Alexia, Eva

name: Clovis Philippe D’Aubigne

age: 22

citizen? upper or lower schooling?: citizen

previous residence: born and raised in St. Michel, France

eye color: blue

hair color: naturally chestnut brown, but he keeps it bleached blonde

height: 5’3

distinguishing features:

`the word “lovely” tattooed on his right wrist

`a mirror image B (as seen here) directly above aforementioned tattoo

`three “tear mark” tattoos on his left bicep

`piercing below his lower lip, on the left side

`pierced ears

`various small scars along his body

four good personality traits

four bad personality traits

three quirks

important people

historyI was born into a life of fame. My father’s name, while in no way the most well-known, was enough to turn heads, earn requests for autographs, and be gifted the occasional free meal at luxurious dining establishments. I don’t remember ever wanting for anything in those early years. I was the happiest I could imagine being. It was just the four of us in that big house at first: Mama, Papa, Lance, and me. Simone was born when I was only four, but I can still remember her wrinkly red face and thinking that something was wrong because she looked more like an alien to me than a normal baby.

I’d like to say I had a normal childhood. I honestly can’t remember much besides picking out notes on my father’s grand piano and begging Lance to play with me in the back yard. Those times were short-lived, however. I can barely remember my brother anymore, with his sun-streaked hair and spindly legs. I don’t remember his voice, only that he yelled. I don’t remember his smell, only that he left his favourite shirt in the clothes hamper and I slept with it for months, even after the smell of him had faded away, leaving me empty. I used to wonder where he had gone. He was only sixteen when he walked out of our lives and vowed never to come back. I haven’t seen him since and I learned long ago that, sometimes, it’s better to not wonder at all.

After that, the most impactful thing that happened in my life was the day I asked Leanne Cavelli to be my girlfriend. I know what you’re thinking, that’s a lot of time to skip. But it’s not, really. See, I went to school with Lee back then. She was two years below me, but I can remember seeing that beautiful blonde hair and instantly asking everyone I knew who she was. Love at first sight, some might say, but let’s get real. I was seven, and I had a crush. Regardless, nothing stopped me from waltzing up to her one day and declaring, “I need a girlfriend this year. I pick you.” From then on, we were inseparable.

I don’t exactly remember my father becoming ill. I remember the little, insignificant things, but not how they happened or when. I remember switching schools but never being told why. I remember that my father was home more and more, not going on tours, not recording, and that my grandmother came to live with us just after my eighth birthday. I remember the hospital bed being moved into the guest bedroom, the sound of oxygen spurting from the long-hosed machine. I remember being told, “Don’t step on the cord.” I remember trying to see what would happen if I did and hearing a loud buzzing noise from the direction of the machine.After that, I spent more and more time at Leanne’s house.

Nothing that happened during those two years seemed to be a surprise for anyone in our family. I did not feel surprise at the way my father slowly became more and more ill, until he needed help to walk to the toilet and my mother and grandmother alternated feeding him food that he never seemed to finish. Looking back, I think that the reason I remained so calm, at least during that first year, was that everyone else was. We never spoke about what was happening, but everyone else seemed content enough with the situation. I thought that Papa, perhaps, was just getting over a very bad case of the flu. I didn’t understand at first that there would be no getting better, and that what he had was much worse than a mere flu.

What did come to be a surprise, however, amongst the relatively unsurprising deterioration of my father, was my mother’s last pregnancy. I was eight at the time, and my father was in a time of mild improvement. Simone and I—though she was only four at the time—argued over the sex of the baby. Boy, I said. Girl, she said. In a way, we both were wrong, though she was closer than I. The twins were born nine months later, at home so that my father could be there. I wasn’t allowed in, though I desperately wished to watch. About five minutes into the screaming, I decided that it was something I could miss after all. Gran took Simone and I to the Cavelli’s house to stay the night. When we came home in the morning, I had two baby sisters.

I've often wondered whether it's terribly odd that, of all those ragged gasps for air and long periods of exhaustion that my father went through, the thing that I remember most vividly is walking into his room one evening to watch the rise and fall of his chest as he slept. I think that I knew, by then, that Papa being ill was much more than a cold or some passing illness. I knew by then that he would not be getting better, not soon or ever. When he woke, he looked at me and smiled the most tired smile I had ever seen. “Come here, my boy,” he croaked, and I did. I crawled over the bars of that hospital bed and snuggled up next to him. “Papa?” I whispered without looking at him. “I wrote you a song.” Then, before I knew it, I was crying harder than I’d ever cried before or since. He held me and whispered that it would be just fine, Clo boy, just fine. But it wouldn’t, and that was a truth that I could not escape, no matter how many promises were made.

Is it too unreasonable to believe that such an event can change one family so much? I have wondered if my memories are skewed to think that we lost money so quickly, that I remember my uncle coming from Paris for the funeral and whispering to my mother in the far corner of the room about unforeseen expenses. At nine, I was unusually small for my age and no more wise than any other nine year old boy. I was more concerned with the toys I wanted for my birthday than funeral arrangements. I had no concept of what the word “expense” meant, nor did I have a particular desire to figure out for myself. The only thing that I took away from those long months was the incurable, undeniable fact that my father was gone.

I found solace in music. Where it had simply been entertaining before, something that I was both good at and found that I enjoyed, music was now the one thing that I felt tied me to my father. I would spend hours playing my saxophone, praying that he could hear me up there. I scratched out notes on carefully drawn music staffs and kept them in a special folder. I was eleven when I discovered the universe of rap music and turned my interest to this over the classical styles that my father had preferred. By day, I was a normal schoolboy. By night, I took off across the streets of St. Michel with my little cap and rhymed on the corners for money. It was during those nights that I felt most alive. It was during those nights that I began to discover myself for who I was.

Who I was, as it turned out, was not limited to the scrawny boy who cracked jokes at the wrong moments and often forgot to hand in his homework on time. I was not limited to the label that my classmates had quickly placed on me. However, who I was outside of those school walls did not matter to my classmates. They did not see a musician, nor the son of one. They did not see a gentle, good-humoured child who loved to make people smile. Instead, they saw my size (punchable, decidedly), and my financial status (quickly plummeting). It may not have been the largest city with a grand school of millions, but it was large enough for there to be a chain of popularity. And I, as it was, remained at the very bottom, just beside Didier Vasser, the boy with braces who still picked his nose. I was a loser.

Likely everyone knows the sort of things that go on amongst preteen boys, particularly when one is much smaller and best friends with a girl. If one has never been in such a position, surely it would not be too difficult of a thing to imagine. I was tousled, tripped, used as a human punching bag, and pushed head-first into many a toilet over the years. I did what I could to stay out of the way of those who found fault with me, but they seemed to find me nonetheless. I was always careful to leave Leanne and my family uninformed of my treatment. After all, no real harm was ever done. At least, that is, not initially.

I’m not sure that I can call myself an avid believer in fate. There must, certainly, be some sort of “higher power” as it may be called, but to think that events are carefully dictated and pre-ordained… I would be a rather angry fellow if I thought that there was a singe being responsible for my physical state today, not to mention the disappearance of my brother and death of my father. No indeed, I can blame only one person for my condition, and he went by the name of Arman Bontecou. Call it what you will. Wrong place, wrong time, or perhaps the simple term “bullying” can describe what happened. Whatever the case, I was caught one day after school in the path of Arman, who happened to be the one boy I wished most to avoid. He and his goonies, as I had not-so-affectionately called them, seemed to find an immense amount of enjoyment in tormenting me. On this particular afternoon, it seemed that they were on a rampage of sorts. Arman was angry—and, may I simply say that an angry, oversized thirteen year old boy and his friends were something to be feared by a boy like me—and I happened to be his target for the afternoon.

If someone were to ask me what happened that day after school, I would have to say that I honestly have very little idea. I vaguely remember fists and feet and pain, but little else. I was left alone, and wondered for what felt like hours if this is how it felt to die. They tell me that Simone found me that way, bloody and motionless on the yard behind the school. In truth, the thing that I remember most clearly is that I woke up as another boy, one who remained stoic in the face of more adversity than he had surely ever seen. The doctors must have told me a hundred things in the days after, but there is only one thing that I remember hearing: I would never walk again.

Spinal cord injuries are tricky, or so I’ve been told. This particular injury was not the sort that was likely to be fixed by surgery, which would have been an expense we could not afford even if it were an option. As it were, my uncle paid the majority of the bills for us, while my mother continually agonised over how we would ever pay him back for everything that he had done for us. I didn’t put up much of a fuss over the information, at least not outwardly, but I pleaded with the universe each night as I fell asleep to kill me then, rather than make me continue with my sorry existence. For whatever reason, I never did get my wish. However, when I returned to school the next fall, I was somewhat of a celebrity. I never asked what had happened to Arman and his friends; all that I knew was that they were gone.

To be honest, being in wheelchair did not change my life very drastically. I cannot deny that there were changes, of course, but the most noticeable ones were within myself. I went through a period of mourning, or something very akin to one, where I found every excuse to not move and alternated between praying for renewed mobility in my legs and for the skies to carry me away to be with my father. More often than not, I clung to hope for the latter. Between my family and Leanne’s however, it was difficult to remain in this place for long. The return to school helped immensely, where I raced my chair at recess against the class’s best runners and celebrated the fact that I was, miraculously, no longer at the bottom of the food chain. I began to find myself once more, not only in music but in everyday life. I found joy again and quickly remembered how it felt to smile.

Time passed. It seems such a silly phrase to add, but that is the simple truth of the matter. I grew—though not much—and gradually began to see certain aspects of life through different eyes. And, when I say certain aspects, I really mean the female population, specifically Leanne. She bloomed into what was most certainly the most beautiful young woman to ever walk the face of the earth. I found myself staring at her when we were doing homework and finding every excuse to touch her, even if it meant pretending to save her from spiders at least three times per week. Meanwhile, our families were, unbeknownst to us, waiting eagerly for something to happen. Four years passed from the accident before I asked Leanne if she could ever think of me as more than a friend. Four years. After the initial decision, I received a number of playful swats from the women in my family as they exclaimed, “Clovis Philippe! What on earth took you so long?”

I can say with full candidness that those few years were, by far, the best of my life. It may not have been the most conventional or worry free relationship, but Lee and I simply… worked properly together. No matter the arguments or times of emotional struggle in our lives, we always made it through, and generally with smiles on our faces. I always did love to make her smile. She did the same for me, with her gentle hands and warm smile. She encouraged me, day after day, to find new ways to overcome my handicap. On more than one occasion, she found a way for me, then took my hand gently led the way.

I don’t think that I will ever understand what I did to chase Leanne away. It was the spring, less than a month before her graduation—I had, meanwhile, forgone university entirely and chosen to take up a job as cashier in a small market while I attempted to make notice of myself in the music industry—and she insisted that she would be leaving and did not wish to hold me back. No, I may not wait for her. No, I may not come with her. She swore, during her bullshit-filled speech, that it was not my doing, but I knew that this could not be true. If I hadn’t done anything wrong, then she would still be here, in my arms. Instead, she remains a memory, a girl who resides in the stars and comes to visit me in my dreams each night as I fall asleep to their melodies.

if you could be anywhere, where would you be? “Back in time. I would be eight again, walking my best friend home from school. I would stay in those moments forever if I could.”

character’s play-by: Luke Worrall